Why I love maps

Many years ago, I briefly considered training to be a cartographer. This didn’t come from any aptitude in geography. It was, rather, that I couldn’t figure out what job I might enjoy, there happened to be a masters in cartography at my local university, and I had a growing fascination with maps.

Deep down I knew this was a terrible idea. It really was more of a thought experiment – a “what if?”. But my love of maps never left me.

At the core of both the appeal and unlikely success of this fleeting plan was probably the fact that I have absolutely no sense of direction.

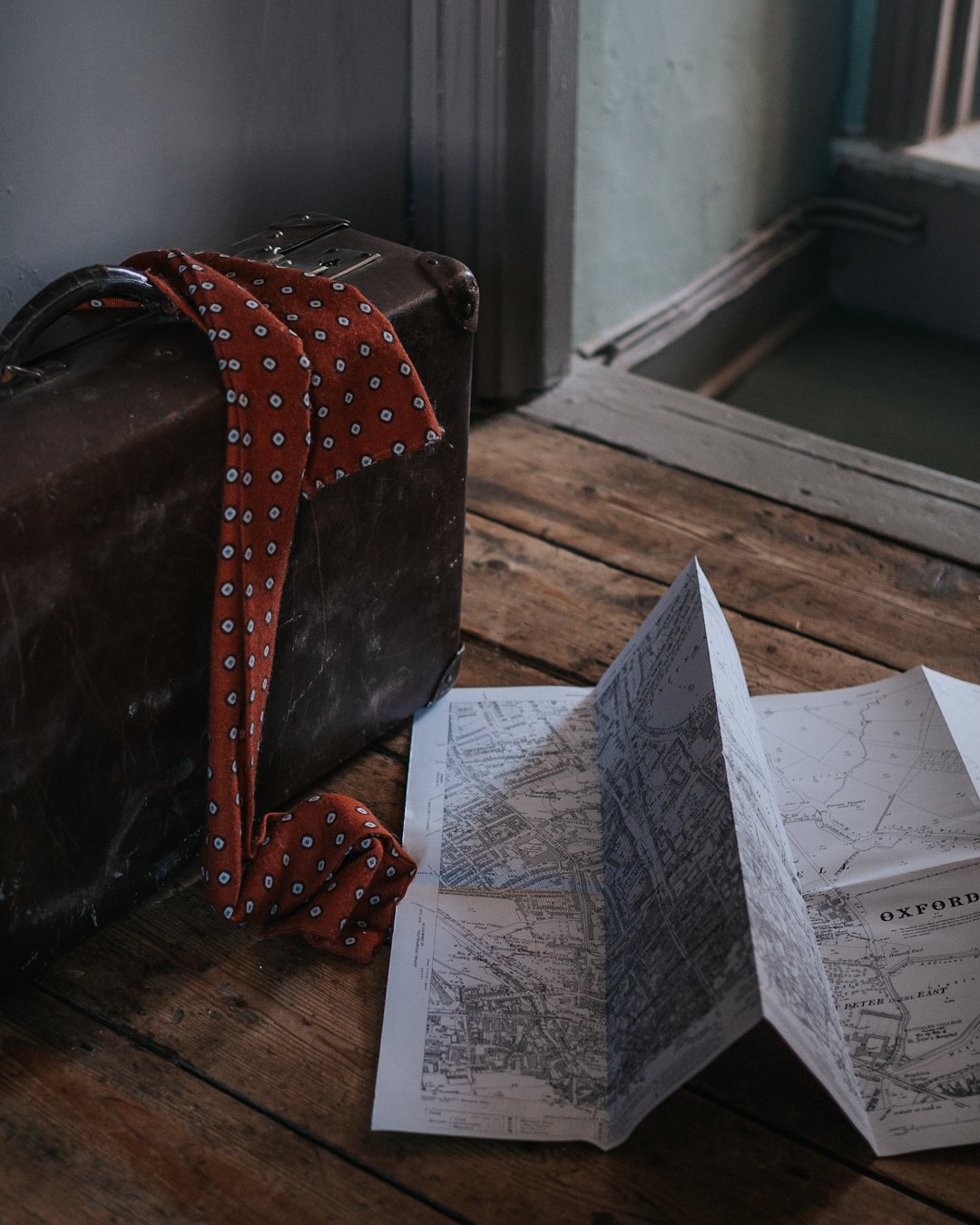

Maps have always been absolutely essential to me. I simply would never manage to get anywhere without them. I have trouble picturing anything based on descriptions, so find being given directions completely confusing. I need it down on paper (or screen) in two dimensions. Flattened, simplified, made comprehensible – and easy to refer back to, again and again.

I believe maps are the ultimate graphic design product. Nowhere else do information and beauty come together so perfectly. Not that they are ever actually ‘perfect’, but the imperfections and compromises only make them richer and more interesting. The impossibility of creating a perfect map is precisely what makes them utterly wonderful.

Maps can be works of art and propaganda. They distort the world, flattening and simplifying it to make it intelligible, and in the process, deliberately or accidentally, shape how we look back at their three-dimensional models.

The London Tube map is a successful example of elegantly aiding navigation while creating, at least in someone like me with little sense of actual space and distances, a fictionally shaped city. The classic Mercator projection word map that we are so familiar with was a breakthrough in transposing our spherical planet to a flat surface, but it is guilty of engendering our wildly inaccurate perceptions of the relative sizes of countries.

The fictional and factual have also always mingled in maps, from depictions of fantastical creatures based on early explorers’ tales, to deliberate ‘mistakes’ introduced in order to protect map copyright, as well as maps of entirely fictional places. These start interacting with the real-world, three-dimensional version, as through tourist maps based on the locations of books and films.

Maps tell stories about the places we inhabit or imagine. They have a viewpoint, promote a narrative, curate information and make it visual: land use, politics, tourist sights, cycle lanes… even the most mundane, utilitarian maps do this. Looking back at historic maps can also reveal how places have changed and give clues about past lives and unfolding events – a story told in layers.

With a little imagination, maps can also create entirely new worlds, through the choice of what to show, and how to show it, in colours, typefaces, lines and illustrations.

Perhaps the ultimate map, in that sense, is the incidental hand-drawn map – the kind of map you sketch on a piece of scrap paper to give directions or explain a story to someone. These maps have it all: the personal, the narrative, all the idiosyncratic beauty of mapping.

Further reading

The Mapmakers, John Noble Wilford

Mrs P’s Journey, Sarah Hartley

Archipelago: an Atlas of Imagined Islands, Huw Lewis-Jones

From Here to There, Kris Harzinski